From “lowkey” to “unhoused”: The story behind USC Annenberg’s style guide

It started as an experiment and has grown into a style guide for language learners and language leaders.

By Laura E. Davis, founder of Stylebot

It’s easy to feel discouraged about the future of media and journalism today: Misinformation and low public trust plague professionals who work hard every day to provide truthful, thoughtful and useful information. I feel fortunate, however, to have spent the last seven years as a professor at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism, a newsroom full of hope and possibility that fuel insight into how our industry can — and needs to — change for the better.

Putting these insights into practice requires journalists to challenge our assumptions and lean into the future, whether we feel ready to or not. At Annenberg, part of the way this work has taken shape is in the form of a new style guide that began with a format shift and has evolved into something more: a new kind of style guide that’s informed and inspired by the next generation of writers.

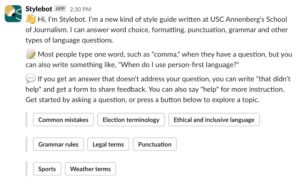

When a faculty team at Annenberg decided to start a style guide that would be accessible on Slack, we really didn’t know what we were in for. We quickly learned two things:

1. People have very specific editing questions, and not necessarily the ones you’d expect.

2. The future of language is here, and students aren’t looking back.

The USC Annenberg Style Guide, in a way, launched as an accident and an experiment. In an effort to get students more engaged with the editing process by allowing them to ask questions to Stylebot and get an instant answer, we needed to write style guide entries that were more conversational. That part we knew. But we didn’t anticipate the types of questions students would ask, or what kind of answers they would need for the information to actually stick.

Language learners

We now say that the USC Annenberg Style Guide is a guide for language learners and language leaders. I’ll start with the language learners part: Most style guides are written for a subset of experts, people already well-versed in basic language rules and who have the time, knowledge and patience to dig up reminders or seek out answers. They know how to find what they need in a style guide, and what they need to look up in the first place. When we distributed a spreadsheet and a Google form to crowdsource questions from students, and when we would just talk to people about what we were doing, we learned that people needed answers to seemingly basic questions such as, “Can I start a sentence with of?” and “When do I use me and when do I use I?”

My first reaction to these types of questions was, “That’s not what a style guide is for!” But our faculty team — which at the time comprised me, Jenn de la Fuente, Edward Lifson and Henry Fuhrmann — didn’t take this attitude. After all, we were there to help. So we dutifully set out to write entries that could answer students’ language questions with responses that were both fun and informative.

As we wrote the guide, we also asked dozens of people about their copy editing habits and attitudes. When we would ask people what they think makes a good style guide entry, the answer almost always included one concept: examples. This, of course, is a common feature in many style guides, but what makes Annenberg’s guide unique is that we almost always include an example in our entries, no matter how seemingly simple the rule.

Even if you’re a professional, there are no stupid questions when it comes to writing. Our guide will readily offer you advice or review on appositives, capitalization and dangling modifiers. We might even (*gasp*) add a little fun to the process.

Language leaders

For us, this fun isn’t trivial, though. It’s a gateway for engagement with the heart of our work, which drives our mission and the deeper purpose of a style guide.

We didn’t get to where we are with the English language by sticking to an unchanging set of rules. Virtually everyone who speaks and writes in a language participates in moving it forward. So while it’s easy to write off the language “the kids” use these days or poke fun at them for lack of punctuation, the reality is that today’s emerging trend is tomorrow’s standard form, as linguists will tell you.

The USC Annenberg Style Guide bridges this gap instead of fighting it and embraces that today’s writers aren’t just thinking about one platform anymore.

Another way we bridge the generational language gap is an important fact that we stumbled upon when we were conducting our research of people’s copy editing habits and attitudes: The content and advice in style guides can make younger writers feel disconnected from the process. In interviews, we heard things such as, “I will forget about [copy editing] when I’m using it in actual writing…because sometimes it’s not really the way people talk about things.”

So instead of ignoring the fact that many people write “lowkey” as one word, we acknowledge it and provide advice. Of course, we always take care to limit audience confusion, as clarity is a key consideration in our decisions, but we at least offer you some guidance.

Sometimes these one-or-two-word decisions are lighthearted. Other times, they are deeply important both for our newsroom and for the greater good. Earlier in this piece, I mentioned Henry Fuhrmann, a trailblazing editor who died in September. Anyone who knows Henry’s work will know what he taught the industry about hyphens in racial and ethnic identities, writing in 2018 that “their use…can connote an otherness, a sense that people of color are somehow not full citizens or fully American.” Henry was a mentor of mine dating back to our days working together at the Los Angeles Times, and his work on this issue and others helped pave the way for Annenberg’s guide to rest on the foundation of the more innate understanding our students have about the consequences of word choice in their everyday speech and in mass media.

One entry that comes up a lot when I talk about the USC Annenberg Style Guide is our guidance on homeless vs. unhoused. We worked with reporters in our newsroom on crafting this guidance, which, like all other facets of the English language, will continue to evolve but provides a snapshot of where we are today.

Annenberg’s style guide is one step in journalism’s journey forward. The product of years of experimentation and research, it keeps the best of media and journalism’s traditions while embracing the future.

“Stylebot has been really invaluable. Truly this has been such a great tool.”

Shayna Posses

Copy editor

“Stylebot helps make the process of learning about style…much easier for both the students and me.”

Frank Russell

Assistant professor of journalism

“It’s so much more user friendly and intuitive for our generation. “

Charlotte Pruett

Former student